In my previous post, I calculated the size of the amounts that could be allocated to the degressive area-based income support payment using the minimum and maximum amounts of aid per hectare proposed in the NRPF Regulation of 130 EUR and 240 EUR, respectively. This payment is intended to provide area-based income support for eligible hectares to farmers to address income needs. The purpose of the exercise was to examine the potential allocations to other CAP instruments, for example, agri-environment-climate actions, depending on how much Member States allocated to the degressive area-based payment.

The limitation of that calculation is that it assumed that all hectares would receive these amounts, and thus it took no account of the potential impact of degressivity and capping. In this post, I try to provide a crude estimate of the likely impact of degressivity and capping for several Member States. It turns out that the degressivity and capping rules, though they seem sharp, will have a limited impact in practice in many countries.

In this post, I am only concerned with the identifying the potential impact of the degressivity and capping rules. I do not discuss the policy intent of the proposal, whether this kind of targeting makes sense, or whether it is well designed for its purpose.

Degressivity and capping rules

The rules proposed for degressivity and capping are set out in the draft CAP Regulation Article 6 (3) and 6(4).

3. The total amount of payments per farmer established in accordance with paragraph 2 shall be degressive in accordance with the following rules:

(a) Member States shall reduce the annual amount of the area-based income support exceeding EUR 20 000 to be granted to a farmer by 25 % where the amount of the area-based income support granted to a farmer is between EUR 20 000 and EUR 50 000;

(b) Member States shall reduce the annual amount of the area-based income support exceeding EUR 50 000 to be granted to a farmer by 50 % where the amount of the area-based income support granted to a farmer is more than EUR 50 000 and not more than EUR 75 000;

(c) Member States shall reduce the annual amount of the area-based income support exceeding EUR 75 000 to be granted to a farmer by 75 % where the amount of the area-based income support granted to a farmer exceeds EUR 75 000.

4. The total amount of area-based income support shall not be higher than maximum EUR 100 000 per farmer per year. In the case of a legal person or groups of legal persons, the capping shall cover all holdings under the control of one legal or natural person.

Although the legal wording is not clear, I interpret this to imply a tiered system of deductions. That is, for a farm that would otherwise be eligible for a payment of €110, 000, there would be no deduction on the first €20,000, a deduction of 25% on the amount between €20,000 and €50,000, a deduction of 50% on the amount between €50,000 and €75,000, a deduction of 75% on the amount between €75,000 and €100,000, and the removal of any payment amount above €100,000.

We should also recall that Member States can differentiate this payment by groups of farmers or geographical areas. Such differentiation would impact on the distribution of payments between farmers and thus on how degressivity and capping would work. As we cannot take account of differentiation we assume each hectare receives the same uniform payment.

Methodology

But this is only the first of many assumptions that are needed to devise a workable model. As the payments are linked to area, ideally we would like to have the distribution of all holdings in a country by their eligible area. We could then apply the assumed payment per hectare to derive the total payment per farm. We would then apply the degressivity and capping formula described in the previous section. Only Member State administrations and possibly the Commission have these data, so for the outside observer we have to make do with the information in the public domain.

The most relevant information is the distribution of CAP beneficiaries by payment size class published annually by DG AGRI. In a previous post I described some data from the latest report for the 2023 financial year which relates to payments farmers received in 2022. This was the final year of payments under the previous CAP Regulation before the current CAP entered into force.

The report provides tables showing payments for all direct payments, decoupled direct payments and coupled direct payments. For area-based payments the information on the distribution of decoupled payments is what we need. In 2022, this included the basic payment scheme, the single area payment scheme, the greening payment, the voluntary redistributive payment, the young farmer payment, payment for areas with natural constraints (which could be financed by Pillar 1 as well as Pillar 2 in that CAP), and the small farmers’ scheme.

The payment data are grouped into payment classes. We assume that all holdings within a payment class receive the average payment in that class. This assumption will influence the impact of the degressivity formula and implies that our results will be conservative and underestimate somewhat the impact of the formula (see technical note at the end of this post).

Applying the payment amounts per hectare for the degressive area-based payment results in total potential amounts for area-based income support that are different to the 2022 amounts paid in each Member State in 2022. I therefore scale the average payment in each size class to reflect the difference between the projected payment after 2027 and the actual payment in 2022. The assumption here is that the distribution of area-based payments after 2027 will be similar to that observed in 2022.

I then apply the degressivity and capping thresholds to these new projected average payments in each payment size class to derive the potential ‘savings’ that can be reallocated to financing other CAP instruments.

Exploration of results

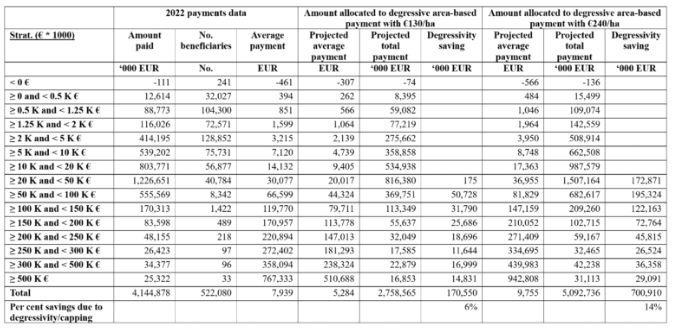

Table 1 shows the results of this exercise for Spain. Spain has an average decoupled payment per beneficiary close to the EU average (which was €6994 in 2022) and also its degree of concentration of payments is close to the average – the top 20% of beneficiaries receive 78% of total direct payments support. The potential savings from applying the proposed degressivity and capping rules are estimated at between 6% and 14% depending on the overall allocation to the degressive payment. The savings are higher when the average payments per beneficiary are higher, as this means that more beneficiaries are pushed into the higher payment classes where the degressivity bites more. Nonetheless, what the exercise underlines is that the amounts involved are not enormous. Degressivity and capping will not cut the area-based payments in Spain in half, for example, freeing up this money to be spent on other CAP instruments.

How the table is constructed: The 2022 payments data are taken from Commission, Indicative figures on the distribution of aid by size class, financial year 2023. The distribution of average payments and total payments by payment size class under the projected allocations for the degressive area-based income support under the minimum and maximum payment rates per hectare are obtained by scaling the 2022 figures in relation to the total projected allocations for the degressive payment. These total allocations are taken from Table 1 in the blog post http://capreform.eu/commission-proposal-could-allow-significant-increase-in-cap-basic-payments-in-many-countries/.

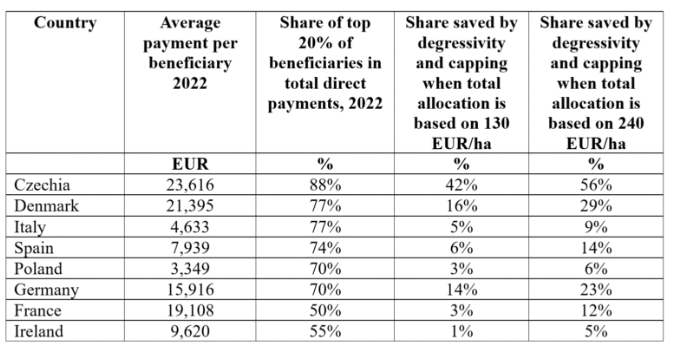

To check whether Spain might be a kind of outlier, I applied the same methodology to a selected group of EU Member States (there is no difficulty to add the remaining Member States and I provide the template for the workbook in a link in the technical note annex). The countries are chosen to reflect differences in the average payment per beneficiary and the degree of concentration of payments in 2022, as these are the two parameters which have the most influence on the percentage savings likely to be realised by degressivity and capping. Table 2 shows the results, where the countries are ranked by the degree of concentration in total direct payments.

The results show that Spain indeed sits comfortably in the middle of the table. Czechia is a country with both a high average payment and a very high payment concentration rate. Degressivity and capping would have a uniquely large impact in this country, potentially reducing area-based payments by between 42 and 56% which could then be allocated to other CAP instruments (any money saved by degressivity and capping remains ring-fenced for other types of CAP income support). Denmark has a similarly high average payment per beneficiary but payments are less concentrated. As a result, the potential savings brought about by degressivity and capping drop to between 16 and 29% which can be allocated to other CAP instruments.

The role played by the average payment per beneficiary and the degree of concentration emerges clearly when we compare the four countries Italy, Spain, Poland and Germany. Italy and Spain have similar concentration rates but the average payment is higher in Spain. So while Spain could save between 6 and 14% through degressivity and capping, these shares drop to between 5 and 9% in Italy.

The comparison between Poland and Germany is even more clear-cut. Both have the same rate of payment concentration but average payments are almost five times higher in Germany than in Poland. The consequence is that degressivity and capping would result in savings of between 14 and 23% in Germany, which is closer to Denmark in this respect, while in Poland the savings would be much smaller at between 3 and 6%.

Finally, we compare the results for France and Ireland. France has the least concentrated distribution of total direct payments in the EU (apart from Luxembourg) but a much higher average payment per beneficiary compared to Ireland. This means that degressivity and capping could result in savings of between 3 and 12% in France, but only between 1 and 5% in Ireland.

Conclusions

In this post, I have used the available public information on the distribution of area-based payments to estimate the potential impact of degressivity and capping on the funds that might be allocated to area-based payments for income support in the proposed CAP. The interest in this question is because, assuming a fixed CAP budget at the minimum ring-fenced amount of €296 billion, the more funds that are allocated to area-based payments, the less are available for other CAP instruments such as agri-environment-climate actions.

Two scenarios are examined, based on the minimum and maximum amounts for area-based payments per hectare in the NPRF Regulation. By linking these payments per hectare to the total Potentially Eligible Area in each country we can derive the potential allocation to area-based payments after 2027 (this calculation and the results are described in detail in my previous post).

By assuming that the distribution of payments will remain the same as for area-based payments in 2022, the last year of the previous CAP, and by assuming that all holdings in a size class receive the average payment in that size class, we can derive the potential impact of applying degressivity and capping to the area-based payment amounts after 2027.

The results show that the impacts will be very different across countries, depending on their average payment per beneficiary and the degree of concentration of their payments. The higher the average payment, and the more concentrated these payments are, the greater the impact of degressivity and capping. Czechia is the outstanding example among the countries I have selected here, where potentially the funds it can use for area-based payments will be reduced by around one half, so these funds would become available to use to finance other CAP instruments. In Denmark, which is close to Czechia but still with both lower average payment and a less concentrated payment distribution, the impact of degressivity and capping drops to around one-quarter of the area-based payment amount.

These countries show the greatest impacts. Impacts for other countries are much smaller. For France and Ireland, the savings vary between 1 and 12% but these are two countries with among the least concentrated payments distribution. I have not attempted to calculate an EU average, but my estimate is that it might lie between 10 and 20%. This will depend both on the overall payment rate per hectare that countries choose to establish for their area-based payment, but also on the extent of differentiation between farm groups and geographical areas that they establish.

These figures are probably smaller than many readers had imagined. The degressivity and capping rates are much more aggressive than what has previously been proposed, and yet their impact in reducing the potential area-based payments is relatively limited. The inference I draw is that relying on degressivity and capping to release sufficient funds to finance other CAP instruments including agri-environment-climate actions may well be a false hope.

Technical note

The two key assumptions behind the calculations in this post are (a) that the distribution of area-based payments after 2027 will reflect the distribution of decoupled payments in 2022, and (b) that we assume that all holdings within a payment size class receive the same average payment of that class. The former assumption can be criticised because the distribution of payments in 2022 was influenced by factors that are no longer relevant (for example, the continued existence of historic payments in some Member States and different ways of implementing the greening payment), but it is the second assumption that is likely to have more impact on the results. There are two reasons to expect that this methodology may underestimate the likely savings from degressivity and capping.

One situation arises where the average payment in a size class falls just below a degressivity threshold, let us say the threshold of €20,000 even though the payment class has the range, say, €15,000 to €40,000. This implies there would be no savings attributed to degressivity in that class, even though some holdings will receive payments about the €20,000 threshold.

The second situation is where the distribution of payments within a size class has an upward skew, meaning that most beneficiaries are located towards the lower end of the payment class range, but there are a few beneficiaries with payments closer to the higher end of the payment class range. In this case, the average (mean) payment per beneficiary is above the median payment. In this situation, applying the marginal rate deduction for each beneficiary for amounts above the threshold will yield greater savings than applying this rate to the average payment and then multiplying by the number of beneficiaries in the class.

For these reasons, the estimates of savings from degressivity and capping are likely to be conservative and to show lower figures than if we had access to the individual raw data.

I provide here the workbook and data I have used to make these calculations which readers can use to also derive results for other countries not considered in this post.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

O artigo foi publicado originalmente em CAP Reform.