The Russian unlawful attack on Ukraine in February 2022 and the following blockade of Ukrainian ports have severely affected global grain supply chains. With Ukraine being a major world exporter of corn, wheat, sunflower and barley, it was imperative for the international community to find solutions to get Ukrainian production out of the country in order to ensure global food security.

The responses to this issue consisted in the set up of “solidarity lines” by the European Union in May 2022, followed by the implementation of the” Black Sea Grain Initiative” in July after an agreement between Ukraine, Russia and Turkey under the supervision of the United Nations. More than one year after the breaking of the war, this paper aims to evaluate the efficiency of these mechanisms, and to take stock of the dynamics of the Ukrainian grain market.

The European solidarity lanes

In response to Russia’s maritime blockade on Ukrainian ports, the EU mobilised in May 2022 the so-called “solidarity lanes”. The aim was to facilitate the export of Ukraine’s agricultural products to compensate as much as possible for the loss of sea routes.

In practice, it consisted in the search for other ways to export Ukraine’s agricultural products via alternative land routes and EU ports, and the set-up of better transport connections, faster customs operation and new storage on EU territory.

Since its first exports, the solidarity lanes have been able to unblock around 29 million metric tonnes of grain to be exported in the EU by road, rail or vessels using the Danube delta.

In the framework of the solidarity lanes, the EU market has opened to Ukrainian imports, resulting in an unprecedented flow of Ukrainians products to eastern Europe. This sudden and significant influx has created tension locally, as large quantities of grain flown in areas with limited storage capacities (compared to the new needs) and high logistic challenges to be overcome to export them while at the same time storing and transporting local productions. Confronted with this issue that affects the Member States differently in the single market, and having assessed the pressure on local prices from these tensions in the logistical chains from the increased transit of products from Ukraine, the Commission has proposed on 20 March an aid package of €56,3 million for farmers in the most affected countries by a drop of local market prices (Poland, Bulgaria, Romania). The payment is expected by 30 September 2023.

The Black Sea Grain Initiative

The Black Sea Grain Initiative is a mechanism implemented by Turkey, Russia and Ukraine under the United Nations supervision to create a grain corridor in the Black Sea. Signed on 27 July 2022, it allows ships to transport grain from three key Ukrainian ports – Odesa, Chernomorsk and Yuzhny – across the Black Sea after an inspection of the Joint Coordination Centre, a body created in the framework of the agreement. Before its entry into force, it was estimated that 22 million tons of grain were stuck in the Ukrainian ports due to the war.

Originally scheduled to run until November 2022, the agreement was first extended for 120 days before a second extension was announced on 18 March 2023. While the original agreement was supposed to extend the Initiative for another 120 days, Russia unilaterally decided to reduce this period to 60 days, warning that any further extension beyond mid-May would depend on the removal of some Western sanctions.

From its launch to 15 March 2023, the Black Sea Grain Initiative has resulted in the delivery of 927 vessels. Altogether, 45 different countries received over 24 million metric tonnes of grain and foodstuffs through this channel. The detailed country-by-country data can be found in the following table.

| Destination country | N° of vessels received | Quantity of grain exported (thousands of metric tonnes) |

|---|---|---|

| Turkey | 205 | 2700 |

| Spain | 150 | 4300 |

| China | 105 | 5400 |

| Italy | 99 | 1800 |

| The Netherlands | 39 | 1500 |

| Egypt | 39 | 842 |

| Greece | 26 | 156 |

| Tunisia | 25 | 560 |

| Libya | 22 | 451 |

| Israel | 22 | 679 |

| Romania | 17 | 285 |

| Portugal | 17 | 577 |

| India | 14 | 412 |

| France | 13 | 273 |

| Bangladesh | 12 | 655 |

| Belgium | 11 | 519 |

| United Kingdom | 9 | 197 |

| Lebanon | 8 | 71 |

| Germany | 8 | 354 |

| Ethiopia | 8 | 203 |

| Algeria | 8 | 182 |

| Kenya | 7 | 327 |

| Bulgaria | 7 | 69 |

| Yemen | 6 | 206 |

| Republic of Korea | 6 | 326 |

| Indonesia | 6 | 341 |

| Afghanistan | 6 | 131 |

| Saudi Arabia | 4 | 184 |

| Oman | 3 | 86 |

| Marocco | 3 | 36 |

| Viet Nam | 2 | 117 |

| UAE | 2 | 65 |

| Sri Lanka | 2 | 104 |

| Somalia | 2 | 54 |

| Ireland | 2 | 60 |

| Iran | 2 | 126 |

| Djibouti | 2 | 7 |

| Thailand | 1 | 68 |

| Sudan | 1 | 65 |

| Pakistan | 1 | 62 |

| Malaysia | 1 | 4 |

| Jordan | 1 | 5 |

| Japan | 1 | 56 |

| Iraq | 1 | 33 |

| Georgia | 1 | 6 |

| Total EU countries | 389 | 9 893 |

| Total | 927 | 24 654 |

Many third countries have a considerable reliance on Ukrainian grain. Indeed, the countries that have been found to have the highest dependency on Ukrainian and Russian wheat imports, and therefore to be the most vulnerable to these market disruptions, are Somalia (100%), Benin (100%), Laos (94%), Egypt (82%), Sudan (75%), DR Congo (69%), Senegal (66%) and Tanzania (64%).

Ukraine also accounted for half of the supply of the United Nations World Food Programme before the war.

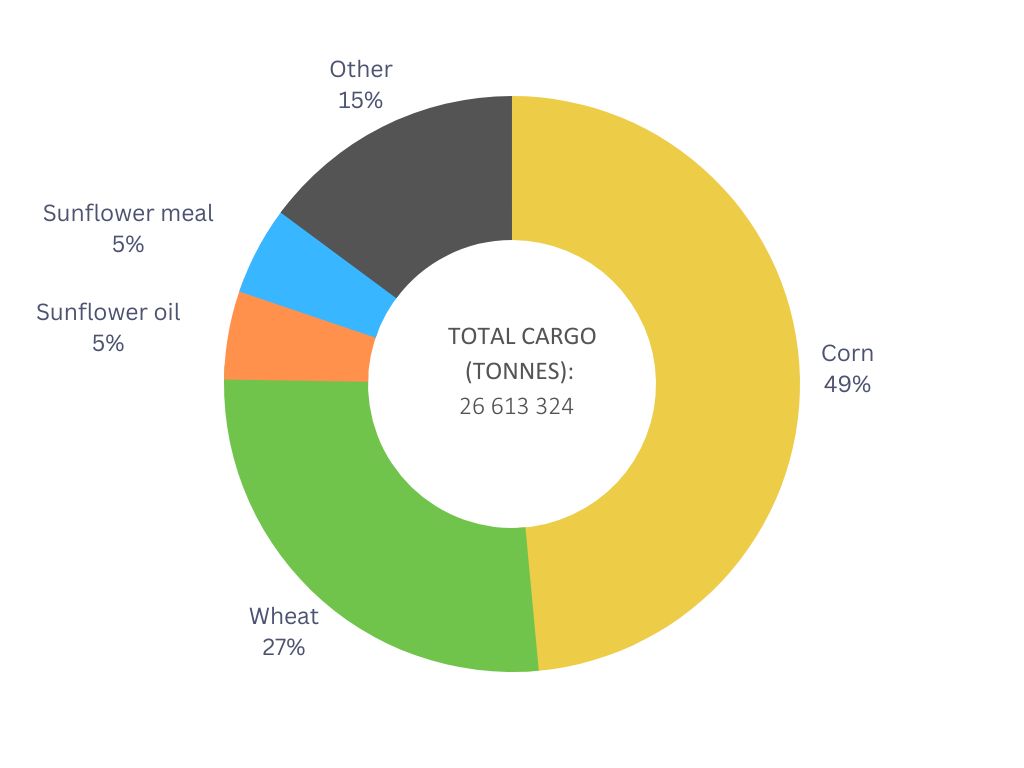

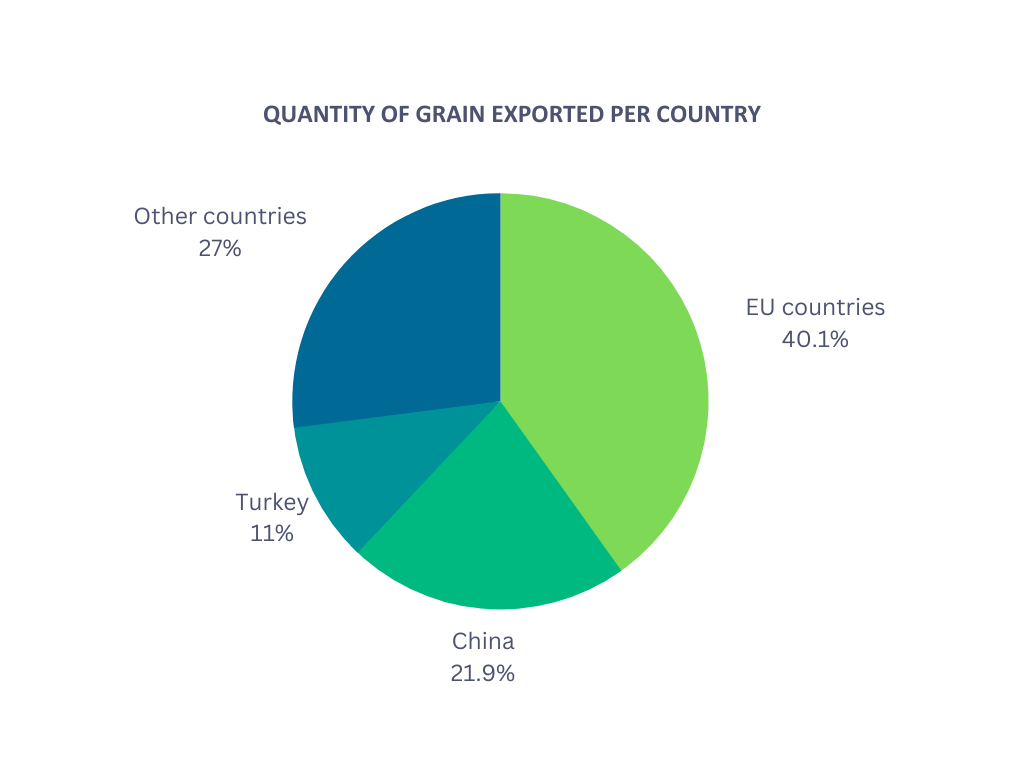

Share of grain exported in the framework of the Black Sea Grain Initiative (mid-March 2023)

In terms of exported cereals, maize accounts for almost half of the exports. This cereal has always been usually mostly exported to China and the EU (for example, it represented 62% of the maize exported shares in 2021 (USDA)). This explains the weight of these two blocs in the total export share.

Wheat constitutes a quarter of the exported volume. It is usually exported to developing countries (notably Egypt, Indonesia and Bangladesh). Since the launching of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, two-thirds of the wheat was destined for developing countries, for which it is the most important and most needed food staple, representing 18.1% of the total shipments of the Black Sea Grains Initiative. Furthermore, it allowed the United Nations World Food Programme to restart shipping from Ukrainian ports, and more than 450 000 tonnes of wheat have been shipped to Ethiopia, Yemen, Djibouti, Somalia and Afghanistan.

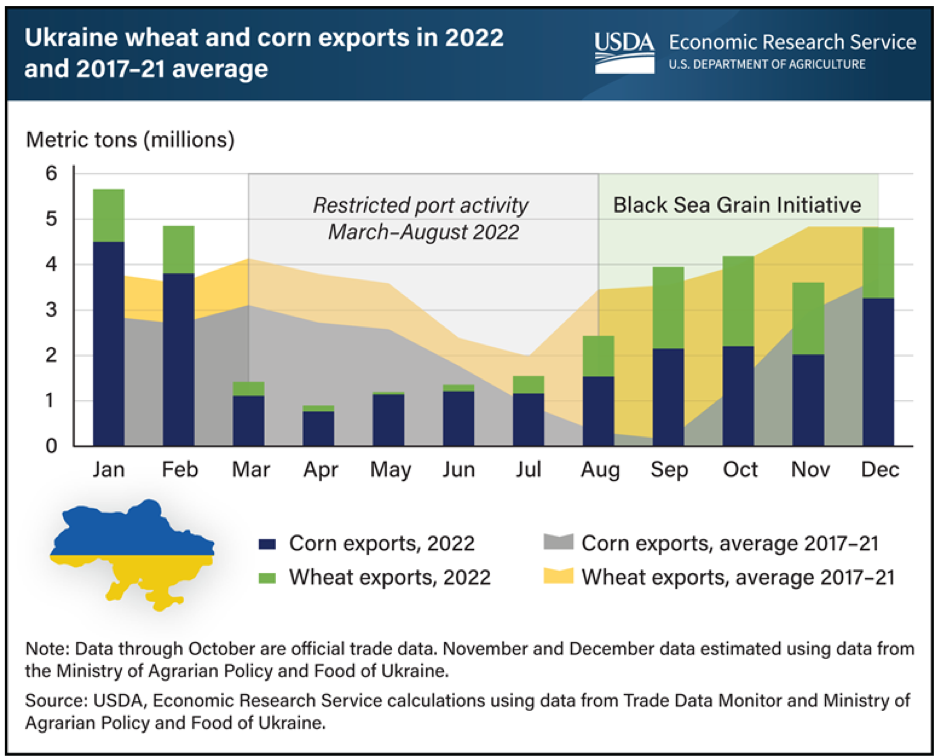

Data shows that the addition of the implementation of the Black Sea Grain Initiative and of the solidarity lanes initiative has effectively allowed Ukraine’s wheat and corn exports to recover.

Both are necessary to export quantities that are required to answer to world market demand.

Estimate of the next harvest for 2023-2024

In 2021, the total land sown in spring amounted to 17 million hectares of crops in Ukraine. These pre-war sowings resulted in decent crops in 2022 despite the difficult conditions and loss of land. In contrast, in 2022 around 4 million hectares remained unplanted due to two main factors:

- Losses of cultivable area due to the occupied territories or the fact that some land is too damaged by hostilities to be cultivated, or too dangerous

- Poor profitability for producers: the efforts to facilitate the transportation of exports have resulted in higher costs. Exports by truck, rail or barge from the west are expensive, while long inspection times and associated demurrage charges have added significant costs to shipments through Black Sea ports. These costs have been largely absorbed by Ukrainian producers in the form of lower prices. Furthermore, the prices of input have risen, further reducing producers’ profit margins and discouraging them from planting for the coming year.

In result, Ukraine’s grain harvest could decline by 35-40 million tons in 2023, including 12-15 million tons of wheat and 15-17 million tons of corn, according to the Ukrainian Agribusiness Club.

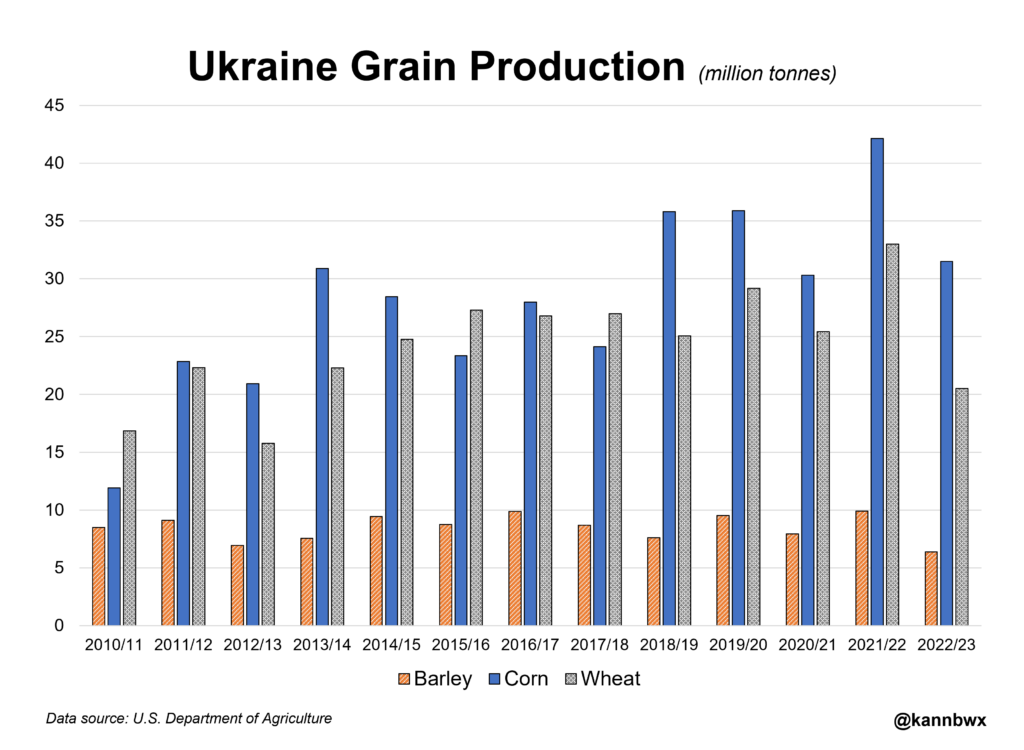

For comparison purposes, the following graph shows Ukrainian maize, wheat and barley production over the last 10 years.

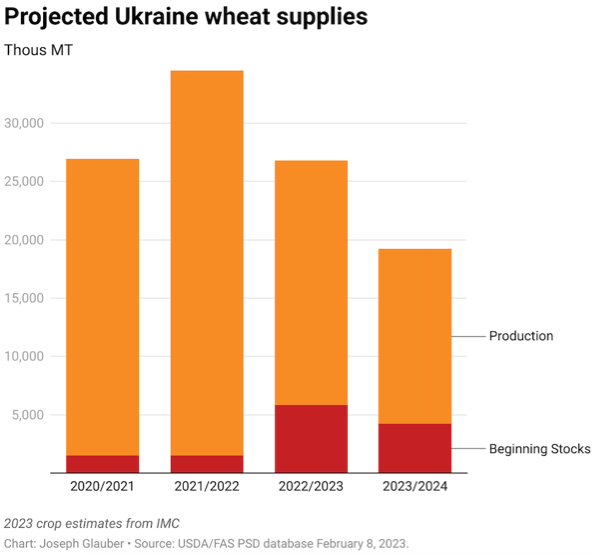

In the future, wheat supplies for 2023/24 (composed of the year production and the stocks from the 2022/23 marketing year) are likely to be almost 30% below 2022/23 levels and 45% below 2021/22 level.

Note that the 2021/22 harvest was an exceptional production year.

Concerning maize, the expected supplies for Ukraine for 2023/24 could be 36% below 2022/23 level and 53% below 2021/22 level.

The issue of storage

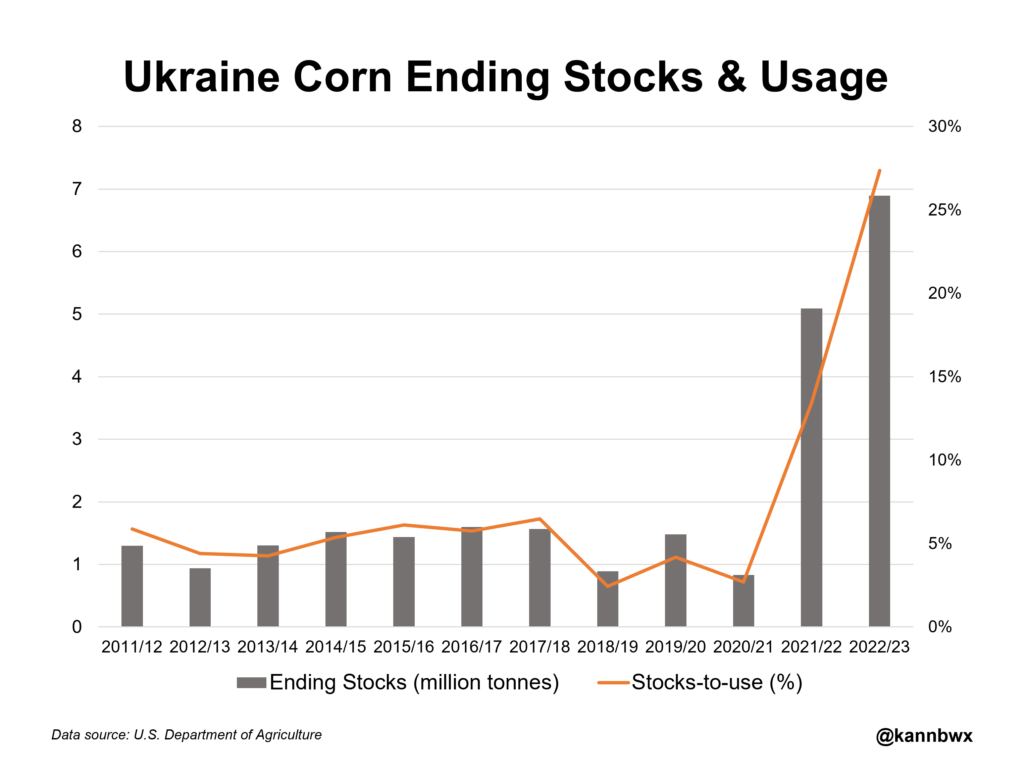

During summer 2022, the Ukrainian storage abilities were questioned, as the grain was accumulating and could not be delivered abroad. This issue has strongly decreased since the Black Sea Grain Initiative: actually, the high grain stocks allowed exports estimates to grow while production dropped.

Before the invasion, Ukraine was exporting nearly 80% of its corn crop annually, preventing large year-end stocks. The Russian blockade has forced Ukraine to stockpile: the USDA’s estimate for the 2022-23 corn ending stocks in Ukraine amounts to 6,9 million tonnes, up from 5,1 million the previous year. This is well above the norm, which averages 1,3 million tons. In addition, the stock-to-use for the year is estimated at 27%, compared to 4% before the war.

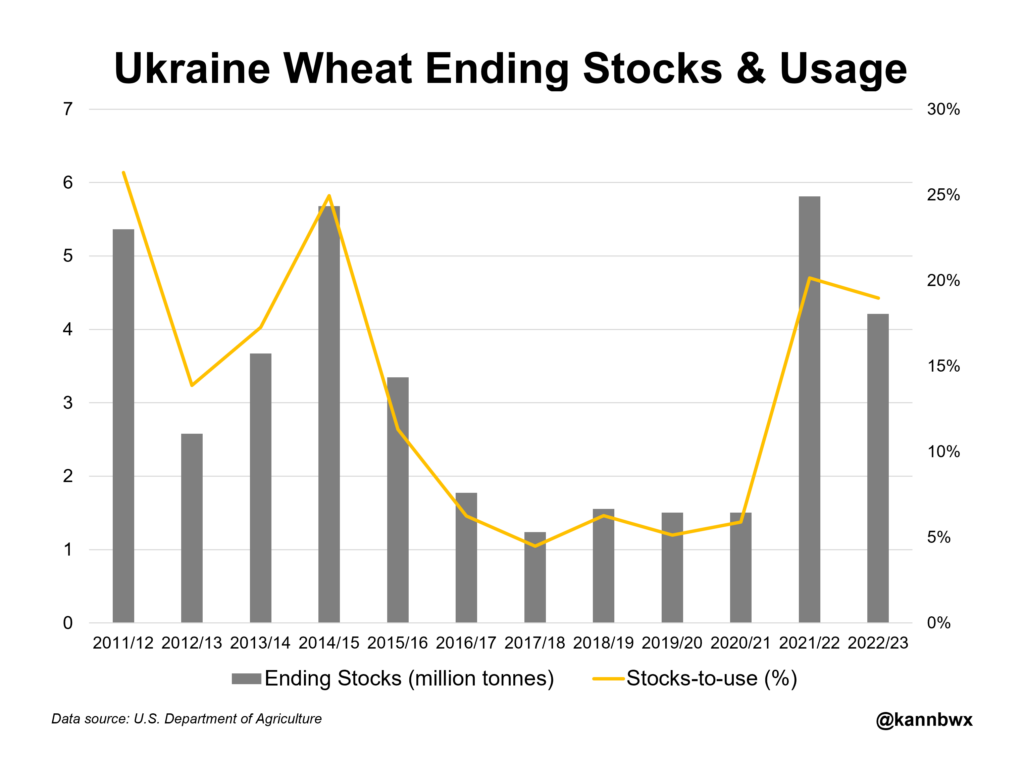

Concerning wheat, the USDA’s estimate for the 2022-23 wheat ending stocks in Ukraine amounts to 4,2 million tonnes, down from 6,8 million the previous years. Here again, the stock-to-use is well above the average of previous years.

Conclusion

The mechanisms set by the European Union and the United Nations have served their purpose in allowing the export of more than 54 millions tonnes of Ukrainian grain. However, the future of the Black Sea Grain Initiative – which has resulted in the export of 25 millions tonnes since August – is conditional on the goodwill of a Russia determined to use it as a leverage to negotiate an easing of Western sanctions toward it.

Moreover, the disturbances created by the war are not limited to the Russian blockade. The harvest of 2022 benefited from the pre-war sowings and was therefore moderately affected by the events, but it will not be the same for future crops. The important stock gathered in 2022 mitigated the gap in the 2022/23 campaign as well.

However, due to the direct and indirect effects of the war, production is expected to decline by 35 to 40 million tons in 2023, with shortfalls of 12 to 15 million tons of wheat and of 15 to 17 million tons of corn. The important stock gathered in 2022 mitigated the gap in the 2022/23 campaign, but in 2023/24 the fall of the production will inevitably affect the international market.

Lastly, with regard to the impact of the Ukrainian products on Eastern European markets, the recently proposed aid package by the Commission may alleviate the pressure for the local farmers. However, the encountered difficulties will remain in these countries, as they are symptomatic of a lack of investment in their infrastructures. It will therefore be crucial for them to be able to invest more in their storage capacities and in the performance of their supply lines on top of the already existing challenge of those countries to develop new outlets for their cereals in their own country, notably based on bio and circular economy.

O artigo foi publicado originalmente em Farm Europe.